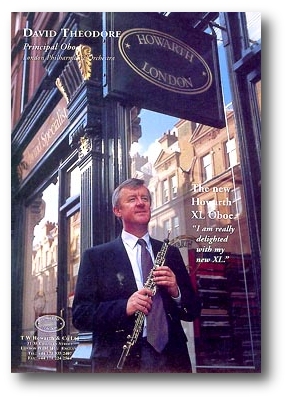

T. W. Howarth & Co. Ltd.

Current Models

Interview with Nigel Clark

July 30, 1982 London

by Nora Post

Arriving in London after the Rigoutat, Lorée, and Marigaux interviews, I was struck by the feeling that the gap between France and England is a thousand times wider than the English Channel. Despite a healthy rivalry between the French makers, the truth is that they have their factories in the same area, the same man makes reamers for each of them, all cases and case covers come from the same place--it's a bit like an oboe makers' cooperative which helps keep prices down. In England, on the other hand, materials as well as labor costs are problems for a variety of reasons, and prices reflect this. Of the oboes in production, I can't think of one which is more expensive than Howarth's. Yet there's also some truth to the old adage, "You get what you pay for." Some of the design changes and ideas at Howarth are certainly fascinating and, more importantly, these oboes reflect a commitment of time in the finishing stages which is tough to match; I believe this is perhaps Howarth's strongest point. W. T. Howarth is managed by two co- directors -- Nigel Clark (director of the London shops) and John Pullen (director of the factory at Worthing.) In addition, Michael Britton joined the firm in 1978, no doubt Howarth's willingness to customize its oboes is due in large part to having a professional player on staff full-time. Describing his role at Howarth's, Mr. Britton seemed to sum up the Howarth experience: "It's all hands on deck here!"

NP: Can you tell me something about the history of oboe manufacture in England ?

NC: Well, a lot of it was derived from Triébert. [1] I think that Morton was the first English oboe firm, in the second half of the nineteenth century. [2] They were the first English manufacturers of keyed oboes in production. Copies of some of the Triébert military system, before the days of the Conservatoire system Morton oboes, were very good.

Hawkes & Son, Boosey & Co.--before they merged in the early thirties--made military system instruments, where what is now the side G sharp key operated the Bb and C keys (which the English thumbplate system is derived from).

The finest quality English oboes started with a company called Louis --The Louis Musical Instrument Company. They were on the Kings Road, Chelsea, in London. They operated between the wars and became famous for their oboes, though they made some clarinets and bassoons, too. The Louis oboe was a direct copy of Lorée--even the name! They just picked a name which sounded like Lorée, although they had no pretense of being French. Louis oboes were all open-holed ring model instruments; they never made the Gillet Conservatoire model, and they were quite popular before the Second World War. Their key work was great--all the keys were really hand-forged, which no one had ever done -- even though everybody says they have. Louis literally took lumps of metal and hammered them into shape; most of the examples of Louis oboes are in fantastic condition today.

NP: Do you have any idea how many oboes they made?

NC: Well, their serial numbers went up to something like six hundred and fifty, but I don't know what they started at. They may have started at ten. Louis, in fact, got bombed during the war and the directors sold the name out to Boosey & Hawkes after the war. Actually, they sold out to the famous English flute-maker Rudall-Carte, who was by then already a subsidiary of Boosey & Hawkes. Boosey & Hawkes became very powerful when they got together, and they used to buy out anyone who began to compete with them. They started doing this before the war; the result was that very few companies started up again after the war, and most of the people who left these other companies went to work for Boosey & Hawkes.

After the war, Boosey & Hawkes decided to begin mass production. They got rid of most of their skilled highly-paid workers. One of these, George Ingram, who had been one of the best men at Louis earlier, wanted to continue in the Louis Co. tradition. He and Frederick Mooney, who had been working before the war at the Selmer clarinet factory, started jigging up to make oboes. The name of Howarth was a long-established name in England, known since the late nineteenth century for woodwind repairs. It was a family of brothers who had several shops in London, mostly in competition with each other! One particular brother, Tom William, or T. W. Howarth, operated a repair shop on Seymour Place--Just down the road. So, after the war, that's where Ingram, Mooney and Howarth started to make oboes. They were there for three or four years, piecing together tools and jigs to start making instruments.

NP: Given the Boosey & Hawkes situation, what made them feel that they would succeed ?

NC: They could see that the new Boosey & Hawkes oboes weren't going to satisfy the professional. And they had seen how successful Louis had been.

NP: What were British players using at the time?

NC: Louis oboes, pre-war Boosey & Hawkes, and one or two Lorées. The English were very pro-English and anti-French at that time, so it was quite unusual to buy anything from Paris. In England the majority of the profession came through the military bands and the training at Kneller Hall, our Royal Military School of Music. It is very British and very traditional, playing traditional English Band music. They all used Louis or Boosey & Hawkes oboes.

NP: What key system was this?

NC: Thumbplate. I think the thumbplate system was established around the turn of the century, when Lorée was making it. Thumbplate is found today in South Africa, New Zealand, Australia, and even Canada. Lorée made very good thumbplate instruments and certainly knew what he was doing. What Louis did was a copy of that. And what we did after the war was a copy of what Louis had done. Though nowadays everyone is continually changing, doing new things, and looking to see what everyone else is doing!

[At this point Mr. Clark took out a hand- written ledger of the earliest Howarth oboe sales.]

The first instrument we made was number 1001, which was sold on the sixth of April 1948. During that first year Mooney, Ingram and Howarth produced thirty-six instruments. But shortly after they got started, there was a falling out over business matters with Tom, who went back to repair work with one of his brothers. But the company had just been registered as T.W. Howarth and they didn't have the money to change the name again, so they were just stuck with the name! Of course, the names of the other two makers, Mooney and Ingram, weren't exactly attractive names! At least the name Howarth was a nice Yorkshire name.

NP: Of course, while the English manufacturing tradition was being established, there were exceptions, most notable Léon Goossens with his 1907 Lorée. How did this happen? A kind of detente?

NC: With the French? Well, there was some rivalry between the makers after the war, inasmuch as the English occasionally saw exhibits of French work, though they never made any contact, never met. It was surprising that Goossens always played on a Lorée. He was quite unusual in that.

NP: So to play a Lorée then wasn't really mainstream?

NC: Oh, no. It was all Louis. I'm not sure how Goossens ended up playing Lorée, not Louis. He was positively the exception. Of course, in 1907 Louis wasn't established, so I suppose there wasn't much else to buy!

Louis tried to make an instrument for Goossens, but Goossens had become very established, very famous with his Lorée, which he liked --although he plays a Louis d'amore. Lorée has never become as established in England as, say, in the USA.

NP: Can you guess why?

NC: Well, they weren't distributed in England after the war until we started selling them about five or six years ago; there was no English dealer until then.

NP: How about Rigoutat and Marigaux?

NC: Marigaux was being distributed. That was the competition from one of the other Howarth brothers, George Howarth & Sons. He imported Marigaux in the sixties and Marigaux made an instrument exclusively for the English market--a ring model thumbplate oboe called their Model 26. But Fred Mooney and George Ingram worked very hard and eventually most of the Louis customers came back to them. All the big names in the orchestral scene here were playing on Howarth after the war. It was just a few of the recital players who travelled and went abroad who did not play Howarth. Other than Goossens, the only other big name was Janet Craxton. She was a pupil of Goossens and, I suppose, because of his influence she also played a Lorée--ring model simple system.

NP: No side F?

NC: No, I don't think so. Her technique was fantastic. So was Goossens'! It shows you don't need all those keys to play well.

NP: And how about the current crop? Are most of them playing Howarth?

NC: Yes. With one or two exceptions, most of the English professionals play Howarth.

NP: Incidentally, do you make a student model ?

NC: Yes, we do. We don't make a very cheap student model; we make a range of plateau instruments in Conservatoire and thumbplate models. The most expensive of these "intermediate" models is about half the cost of the professional model.

NP: I see. What percentage of the Howarth production is thumbplate?

NC: About 80%, of which about half are the dual system -- Conservatoire and thumbplate -- the others are pure thumbplate.

NP: Can you explain exactly how thumbplate works?

NC: Thumbplate is a mechanism operated by the left-hand thumb for playing Bb and C. On a pure thumbplate system, there is no mechanical connection between the first and second joints. So, instead of putting your right hand first finger down to play Bb and C, we take our thumb off. Bb is played only with two fingers of the left hand; C is played with only one.

NP: That's unadulterated thumbplate?

NC: Yes, pure thumbplate. At the same time, the key which you know as the right hand G sharp key becomes a side Bb and C key, doing the same thing as the thumbplate -- left over from the military system. The advantages of the system -- and we do happen to think we're right--is that on a Conservatoire instrument Bb is very stuffy, dull note because you have to use the first finger of the right hand. It's an uneven sound. There's a lot of resistance, which the other notes around it don't have. The C natural becomes very nasal -- a hard, edgy sound. The reason that the Conservatoire system took off, and the reason that Gillet liked it so much, was that it allowed you to keep more fingers on the instrument. Apparently the teachers at the Paris Conservatory didn't like the idea that they were holding the instrument for Bb with just their thumb and two fingers. But to any English person who's learned on a thumbplate system, they consider the Conservatoire system to be so illogical and so "Why should you (when you're playing notes with your left hand) suddenly be using your right hand?" The Conservatoire system makes some passages very, very difficult. You don't have that problem with thumbplate.

The dual system is simply adding a thumbplate to an existing full Conservatoire system by keeping your left thumb on the back of the instrument all the time. Alternatively, you can lift your thumb and play it as a thumbplate instrument. That gives you all the advantages -- a nice clear Bb and a good steady C natural.

NP: How about third octave keys on thumbplate systems?

NC: They don't go together particularly well. Very few people have both; most use semi-automatic octaves here. When we make instruments for export we normally have a third octave--except to America, where third octave isn't standard yet. Of course, Lorée hasn't been a great exponent of third octave, where Marigaux has been; Marigaux invented the third octave.

NP: With thumbplate, it makes an awful lot going on for one finger, doesn't it?

NC: Yes. It is not altogether satisfactory. And very little is known about the third octave. Players don't know when to use it, whether to use it with the back octave or not. Some use it for E, others don't use it till F sharp. So it's still somewhat experimental. Manufacturers have come up with a standard hole size for it, a straight hole like a trill key with a fairly uniform hole size. And really, the opening of the key is so small that to make it work you have only got to make it leak. And, unless the key is well-made with strong metal, it bends. Players tend to strain and squeeze a bit when they get to the top, and they just bend the key in. So the third octave gets bent into the back of the second octave, and we regularly do this repair. At Howarth, we make the key thicker, a hand-forged key instead of a casting or anything else. It's not the perfect design, but then the oboe design isn't perfect anyway.

NP: And you do it primarily for export. Incidentally, what percentage of your business is export?

NC: At the moment it's still very small. Our total production is about twenty professional models a month and another fifteen to twenty student models a month. We could be lucky to sell twenty instruments total this year outside England. We're still working very hard at it. We sell to Japan, Australia (some of these are the old-fashioned English system -- pure thumbplate with open holes), and a bit to the States. For the most part, the export oboes are standard Conservatoire system.

NP: How about import activities? What percent of your business is import?

NC: Well, John and I took over the company when it only made oboes. But we started a woodwind shop and have slowly built it up over eight years. Our own manufacture is probably about one third of the total turnover. The rest is flutes, oboes, bassoons, clarinets, saxophones, music, accessories, and repairs.

NP: Well, then I'd like to ask a question only about your oboes -- what percentage of your oboe sales are Howarth oboes?

NC: Well, that's all changing now because we have gradually been increasing our own production and some waiting lists have come down. A few years ago, there seemed to be shortages of good quality instruments, but nowadays good quality instruments are much more readily available. Now we sell about two to three Lorées and three to four Cabarts a month. Rigoutats were in great demand in England a few years ago, when we couldn't get them; but now that they are more available, the demand dies off. When you can't get something everybody wants it!

With Marigaux we are lucky if we sell six in a year, but we keep them in stock so that we can show the customer everything--Howarth, Lorée, Rigoutat and Marigaux. That way people can always choose an instrument on the merits of what works best for them.

NP: I didn't ask about your materials. How long do you age your wood?

NC: About four years. We're very happy with our blackwood, or grenadilla. Blackwood lasts much longer than the rosewood which was its predecessor, used by oboe-makers in the last century. Rosewood is much softer and has a more limited life -- the bore shrinks more. Of course, the oboe has a limited life -- after all it's only a piece of machinery. People don't like to believe that their oboes are worn out. We had a tradition in England that you bought an oboe when you were a student and you had that instrument for the rest of your life. When we first came into the trade, that was still the thinking. When we heard that in America you change your oboes every couple of years -- like your women and your cars -- it shocked us! Of course, when you look into it, you begin to see the problems that some of the older English players are having, playing on very old instruments. When they do realize that they must move on to a new instrument, it becomes very difficult for them to change.

NP: Yes. I buy an oboe every few years. And, at the risk of being accused of conspicuous consumption, so far I've bought at least one baroque oboe of some kind every year.

NC: And to us that's staggering. Though more and more of the English players are catching on to the advantages of new instruments. We're always making little changes. Hopefully, you'd notice the improvements.

NP: Well my guess is that the players do notice. Tell me, how many people do you have working for you at the moment?

NC: At the workshop, I think it's seventeen.

NP: And what's your waiting list these days?

Going back to the history of the thing for a moment, we were the first ones in England to make the Gillet French Conservatoire system. Hardly anyone had ever seen one here before. The first one was made during the early fifties for Michael Dobson, who was Professor of Music at the Royal Academy of Music. But these instruments were very few and far between. The British "Old Faithful " is this model here, the S2, a pure thumbplate, open ring system. That is what's still used in most symphonies in England. Goossens' oboe is even simpler than that, and so was Janet Craxton's. It has the advantage of giving a very true, round sound. People like the sound and they feel close to the instrument.

NP: Oh, yes. It's almost like playing a baroque oboe--none of this you, the key, the cork, the instrument.

NC: Yes. And it's a bit cheaper and has fewer repair problems.

NP: Of course, it also points out the difficulty of adjusting to one instrument when you are used to something else. I'd probably never be happy with an instrument like that -- I'm so used to all that orthodonture which is the mainstay of my life!

NC: Yes, but most everyone here learned on an open holed thumbplate. So they're used to it. Teachers like it because it forces you to use the correct hand position over the toneholes, which isn't a necessity with the plateau system.

Going back to the early history of the company for just one moment more, in the early fifties Mooney and Ingram moved to Blandford Street, just down the end of the road here. In the early sixties they moved up to the present address. Where we're sitting now was the machine shop and the shop is where the workbenches were. They had just a tiny little place for the customers, right by the window. They usually had between two and three people working for them, making very good oboes with very old-fashioned methods. When labor charges started to accelerate phenomenally at the beginning of the seventies, you just couldn't carry on using those methods. At the beginning, one man made one oboe from start to end.

NP: That puts you in history right there.

NC: Yes. They were very, very skilled people. But towards the end of the Mooney/ Ingram days they had one guy doing the wood, the pillars and turning, and another chap slugging away making parts for keys. They also had the mounters, who would assemble, file the castings, do everything to make the oboe into a working instrument, and then they'd send it off for plating.

NP: You've never done plating?

NC: No. After the war, when things were very difficult because we couldn't get materials, the only thing we could get was silver, so all our early instruments were solid silver keys--about the first hundred and fifty instruments we made.

NP: How much did a solid sterling oboe cost?

NC: About 10 pounds more than a nickel-silver oboe, oh, about 60 pounds or 70 pounds for an oboe. But by the sixties, we were making only nickel-silver oboes. We can't make solid silver with our present production methods.

When John Pullen and I took the company over in 1974, we had three people on the staff besides Mooney and Ingram. It was sweat labor and people were poorly paid. We went to see Alain de Gourdon in 1975 and that opened our eyes; we learned so much from him.

NP: How helpful was he?

NC: Absolutely tremendous. Fantastic. He told us everything we asked, helped us with materials; we certainly admire everything that he's doing. The quality of his work is an example to everybody. And I suppose that it's people like us, the manufacturers, who really appreciate what he's doing. Most people pick up an instrument and play it; they don't know what's gone into it.

NP: If you stacked up all the French oboes, would you feel that the workmanship of Lorée is the best?

NC: Without a doubt.

NP: In what ways?

NC: Well, there are two parts to an oboe. One is how it plays, and that's a combination of the bore and the tone hole sizes and cutting. The second is mechanical. For an oboe to work really well, it has got to cover one hundred percent. The only way it's going to do that is if the mechanism is absolutely perfect --no play between the pillars, no lateral movement; the keys must be rock solid. Alain de Gourdon is a perfectionist when it comes to engineering standards. I'm not sure that he ever trained as an engineer, but I'm sure a lot of engineers could learn a great deal from him. He's introduced new standards of perfection in terms of tolerances you've got to work to. We have to work to match his standards.

NP: Tell me about your gold oboes.

NC: Well the first one was for Malcolm Messiter, about five years ago. I think now he's about to take delivery of his fourth "golden oboe." It's a nickel-silver base, silver plated, and then gold plated on top.

NP: Forgive my ignorance, but why do you have to silver-plate first?

NC: Partly so that he can try the instrument first. It's made specifically for him, but we haven't spent a fortune in goldplating just in case it doesn't work out.

NP: What does the gold-plating cost?

NC: To literally put a flash of gold on an instrument could be done for as little as 100 pounds, but it would wear through in a few weeks. So it's actually closer to 400 pounds; we have to increase the plating for certain keys and that starts to cost a lot of money.

NP: Speaking about Malcolm Messiter reminds me that I wanted to ask you about your own background as a player. I also wanted to ask your age.

NC: I was twenty when John Pullen and I purchased the company, and I'm twenty- nine now. I was brought up in the provinces where my playing was considered to be tremendous! I came to London as a Junior at the Royal College of Music and found that there were little girls five years younger than me who could rattle off the Gillet studies, and I was shocked. I had always fancied being in the business, so I put the two things together. Being a player has helped me to understand some of the problems, to understand the importance of a player's problems with an instrument. Of course nowadays my playing has sort of gone off considerably! Sometimes I'll take an instrument home for the weekend and I'm shocked at how atrocious my technique has become and how out of breath I am. It makes me aware of some of the problems customers are talking about.

Most of our staff are musicians, too, which is quite unusual. Nearly everybody plays something. Michael Britton joined us four years ago. He's a professional player who had been playing in South Africa. Michael is an excellent oboist and really understands the instrument. Nowadays it's often a joint decision between us how we tune instruments.

Of course, when a player picks out an oboe, you should play only the bottom and middle octave and forget about the top notes. They will all come on any oboe, once you understand what type of reed the player uses and what fingerings they have been taught. In England we have a totally different reed style than what is used in America. When we sell a French instrument it is not usually in tune with itself for our way of playing, so we have to make some alterations to the tone hole sizes.

NP: Yes. The first time I played a Howarth instrument, it seemed uneven to me.

NC: An English style reed is more relaxed-- less pressure -- than your reeds. Americans tend to push all the time, and the French instruments are consequently tuned down on the left hand (A, B, Bb, and C). But here we play with a more relaxed embouchure and a French instrument would sound flat on the left hand. When an American plays one of our oboes for the first time, the left hand notes many be on the sharp side. But after ten minutes, they'll adjust the pressure and play it in tune.

NP: When I played a Howarth oboe earlier today, I found that it was lighter than my French oboe, a little less resistant.

NC: Yes, our oboes for the home market have a larger bore than most French instruments--particularly in the bottom joint and the bell. Since meeting many American oboists at the last couple of IDRS annual conferences, we have realized that for the American market we have to make a new instrument. The oboes we have made for Malcolm Messiter have had a smaller bore size, and when American oboists tried his instruments they felt much more at home. We have just started to produce a special Malcolm Messiter oboe specially for the States and already have some orders. The oboe is such a complicated instrument; there is still so much to be done to it and we are still learning. And you must compromise-- it still has to be an oboe, with all the characteristic sounds of each note. I think most oboists, even if they don't have perfect pitch, can tell you what note someone is playing on an oboe. You couldn't do that with a clarinet or a flute.

NP: Do you see any aspects of oboe design that you'd like to change or improve?

NC: Yes. The whole forked F arrangement is a joke. As a compromise during the last few years, we've put on what we call a key F resonance. We wanted a larger bell for a better, cleaner E natural and this allowed us to do it and keep a stable F. The key F resonance was the instant cure -- the only solution. It's expensive to do, but it gives you a perfect E and a perfect F--two of the big problem notes on the oboe. But there is a much better system called the Foreman F. There are some examples of this done by Lorée many years ago. The problem with the present arrangement is basically that your E and D keys are in the wrong place because that's where your fingers are. These tone holes should be much lower. The Foreman system kept the E plate but put the actual hole down lower, opposite the F key. The D key was where the F resonance key is, so no matter how you played F it was still the same. I haven't seen the Foreman F on a Gillet Conservatoire system oboe, and I'd certainly like to give it a go sometime. You play it exactly the same as any other oboe--in fact we did it on some S2 models a year or so ago and people didn't even notice (except that their forked Fs were in tune) --they don't even look at the keywork. Actually that's the most disappointing part of being an oboe maker. You go to tremendous lengths to make beautiful keys and nobody looks at them.

NP: Talking about the disappointments of the profession, what's the worst headache of being in this business?

NC: Trying to make it profitable and still enjoy it. Trying to do it because we love the oboe, but at the same time running a business, which means dealing with the tax man, employing and sacking people -- which is the most appalling thing you've ever got to do. Being a young company, we will have many years to go before we are one hundred percent solvent. It would be nice to work more for ourselves and less for the bank manager and the tax man. We spent so much money moving factories, buying these two shops, machinery, building up stock -- it's cost every penny we've made. But one day we'll be able to sit back and say "This is big enough," and we're not far off it now. You shouldn't sit back at twenty-nine and say "I've done it." I haven't done it yet, though I think we'll hold back for a few years now to consolidate. We've got a very good production system going and we have to let it start paying for itself.

NP: What's the nicest part of the business?

NC: I love the trust between maker and player. We're basically dealing with happy customers and there's a lot of mutual respect. It's great to be able to tell a player, "Take half a dozen instruments away and see how you get on with them," and know they'll be back in the morning. It's fantastic trust, which people in other businesses can't believe. Compared with the saxophone business, for instance--I mean you'd never let a saxophone or clarinet player take an instrument away overnight without paying for it first. Never trust a saxophone player!

I suppose it's all because I love the oboe. It's so difficult that once you've mastered it you're going to stick with it for life. There's no other woodwind instrument like it.

Footnotes:

[1] The Triébert dynasty began with the production of oboes in 1810 by Guillaume Triébert. The first patent for a thumbplate system oboe was granted to the Triébert firm in 1849. (Philip Bate, The Oboe London: Ernest Benn Ltd., 1975, pp. 68, 71-72.) [return]

[2] The Alfred Morton and Sons firm operated between the years 1872 and 1898. (Bate, pp. 72-73.)